Gabo is not dead

Photos and text by Pablo Corral Vega

I’ve heard a terrible rumor. They’re saying that Gabriel Garcia Marquez is dead. Who could think up such a hoax? To say that Gabo is dead is the same as saying that Aureliano Buendía never existed. Or to say that Remedios la Bella didn’t go up to the sky wrapped in a sheet, or that Melquíades didn’t return to the Buendía’s house because the loneliness of death weighed heavily on him. Does anyone doubt the existence of Isabel who sees (in the present, always in the present) the endless rain of Macondo? Or of the angel who ends up stranded on a beach and is mocked by the children?

Gabo’s characters are hopelessly alive. We love them, we hate them, we remember them, we confuse them with the relatives that our grandmother was unable to identify in the family tree. They are part of our family epic. Their delicious and foolish deeds are the deeds of those of us who inhabit this delicious and foolish land; an extreme, exaggerated, baroque, unpredictable, unbridled land of cruelty and lust, crammed with tenderness.

Gabo whispers in our ear, speaks to us with the intimacy of the one who knows our greatness and our nauseating bad smells. “I know you,” he tells us, “I know all the delicious nobodies who came before you. And he shuffles our origins until we have no vanity and pretense left. He goes so far as to say that our town (because after all we all come from a town) of groove boards and zinc awnings, is richer than all Paris and New York, because in our town the real is a thousand times more fantastic than the imaginary.

Can anyone say that Colonel Aureliano Buendía died in the first paragraph of One Hundred Years of Solitude? If he dies, then why do we immediately become enraptured with his life? Gabo teaches us that the past and the future intersect and intertwine. Today you may be dead, but tomorrow you’ll fall madly in love with a beauty.

Gabo built the closest thing to a mythical vision of our America, he told a life story that contains all the stories and all the characters and all the times. But it is inevitable to ask how he managed to generate characters that were more alive, more persistent, closer and more endearing than those in flesh and blood.

It occurs to me that the world is upside down. That it was the characters that gave birth to Gabo, that the Aurelians and Jose Arcadios existed long before him, and that they were the ones that gave the most improbable, the most parrandero, the most exaggerated and imaginative of the Caribbean journalists, the power to conjure them up.

Gabo’s words sound like an incantation, and they slip through the mind provoking a lustful and carnal pleasure. They speak of a territory truer than reality, a territory where death and life walk the streets of Cartagena, rinsed, drunk, holding hands, dancing when they can. Stumbling and kissing.

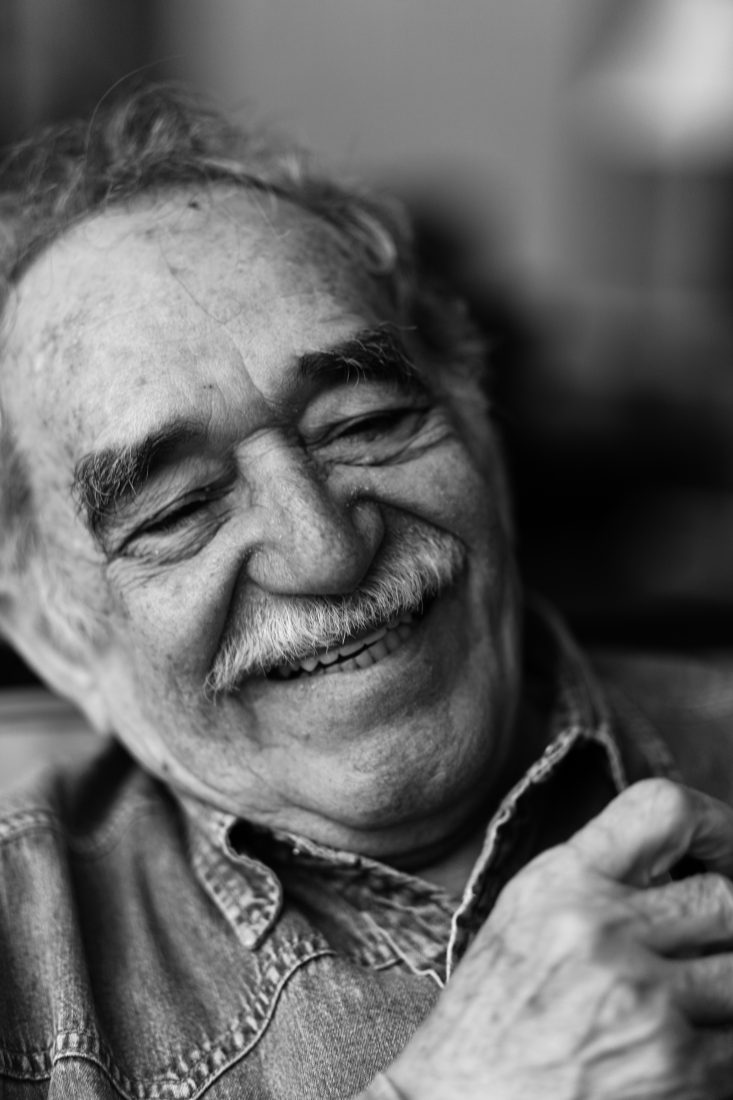

Between laughs Gabo told me that the family thinks that he’s lost, a little bit lost, but the truth is that he plays dumb so that they don’t mess with him… I think that now he plays dead so that they don’t bother him. Because to say he’s dead is unfounded. He’s alive and well, with the Moralito de Valledupar and all the beautiful women who ask him for his autograph and mess up his curly white hair.