Photography as language

By Pablo Corral Vega

The path that a photograph took in the 20th century was short and predictable. An amateur would take a picture with his film camera, send the film to be developed at a local lab, collect the prints and in some cases choose the best ones and place them in an album. A few images were then reproduced to be displayed on a frame or to be given as a gift to a relative or friend. Most of them ended up in a drawer and were rediscovered years later when time and nostalgia gave them back their value.

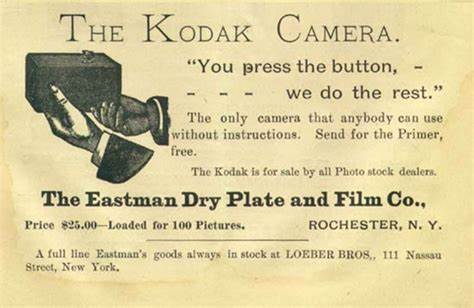

The camera has been present in the lives of countless families since the invention of the Kodak Brownie in the late 19th century. The slogan used to sell it says it all: “You press the button, we do the rest”.

Photography until then had been a cumbersome and expensive process, requiring training to operate the camera, to prepare and place the photosensitive emulsion, to mix the chemicals, to develop the original and eventually to make paper copies from a negative. The Kodak Brownie gave everyone the ability to record their life, with the simple effort of pressing a button.

That first Kodak gave birth to a type of photography whose reason for existence was to collect and preserve private visual memory.

The photographs taken by amateurs quickly became the most precious possession: they are joyful and painful testimony of the passing of time, celebration of affections, living memory of what is no longer there.

Family events were transformed into elaborate camera montages. Photography came to hold a central place in people’s lives. Imagine a wedding, a birthday, a trip where no photos are taken…

Family photographs – the first good that many would save from fire or flood – are relevant only to those closest to the subject. This is precisely why amateur images followed such a short and predictable path: they remained in the dark realm of the intimate.

Photography as an industrial process

The first great wave of democratization in photography, at the beginning of the 20th century, occurred as a result of a technological revolution. The industrial manufacture of flexible and transparent photosensitive material – which can be rolled up – brought photography within the reach of millions, and enabled the creation of the first film camera and the first amateur box cameras.

“You press the button, we do the rest” perfectly explains the state of photography during the 20th century.

And what is “the rest”?

Underneath the little button, so simple to press, was a real iceberg. “The rest” was done by a company that mass-produced the films, a very complex and expensive industrial process. Kodak was one of the world’s great companies for over a century.

But “the rest” was also that collection of trade secrets. Professional photographers achieved – thanks to their knowledge of what is beyond the button – the quality that was normally forbidden to amateurs.

In saying what I am about to say, I run the risk of oversimplifying the complex history of photography in the 20th century: the photos of professionals were published in magazines, exhibited in museums and used as documents of all kinds. In other words, they went beyond the intimate realm and served to record, commemorate and comment on the events of society. Media editors, museum and exhibition curators and professional photographers themselves – in some cases – decided which images were relevant.

There were two parallel worlds. The small, exclusive world of the professionals, who jealously guarded their techniques and secrets, and populated people’s imaginations with images. And that much wider world of the amateurs, whose images -very valuable to those portrayed- were condemned to languish in the same private place where they were born.

The internet as the printing press of the 21st century

The moment we are living now is similar to the time after the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. Before Gutenberg, publishing a book was an extremely slow, expensive and cumbersome business. The monks who copied and illustrated the books were confined to monasteries. Beyond the walls that isolated them from the world, few had access to a book and were able to read.

There was a deep divide between literary languages and vulgar languages. The written language of the monks who copied and preserved the knowledge was sophisticated, cryptic, different from the oral language of the people. With the invention of the printing press, books ceased to be exclusive, a pressing need arose to learn to read (and write) in the vernacular languages. The languages of the people became intermingled with the cultured ones, and literature acquired an unusual vigour. Works and writers whose works would never have been published before the invention of the printing press influenced and transformed society.

It is impossible to understand the contemporary world without the invention of the printing press and the free flow of ideas it made possible.

But printing presses are expensive, difficult to manage, and do not start without the content to be published having passed countless filters. Five centuries later, the Internet offers a personal printing press, that is to say, the possibility of publishing, spreading an idea -any idea- beyond the personal sphere, without a great effort and at an insignificant cost.

Are there too many images?

I have often heard in recent years the idea that there are too many images. It is similar to saying that there are too many words. Words serve a specific purpose, they have missions and functions. Sometimes I write a letter to a friend or a shopping list, sometimes an essay, a poem. Words are never disconnected from the context in which they were expressed or written. The same is true of images.

What we are experiencing is a radical democratization of the image. Digital cameras are cheap and of great quality, we no longer have to pay that onerous toll to Kodak, Agfa or Fuji Film to operate them. “The rest” can be done at home, with easy-to-use tools and minimal costs.

However, digital image capture would not be enough to transform the world of imaging, we have been using scanned photographs for decades. The revolution we are living is in the invention of the digital printing press (the internet), the spread of personal terminals connected to a network of networks. What changes the paradigm is the ability to publish personal images, to take them out of the restricted realm of the private.

The unexpected route of a photograph in the Facebook era

The path that a photograph follows in the times of Facebook is revolutionizing the way we relate, the way we understand ourselves.

An amateur takes a picture with his smartphone (there are already more than a billion in the world), uploads it to Facebook with a series of tags that let you know for whom that specific image is relevant. That picture is seen in minutes by tens, hundreds or even thousands of people. It can be duplicated, resent and shared in other networks and areas. The path a picture takes is long and unpredictable.

A photograph is blind, unable to navigate the virtual world alone. It needs to be accompanied by words. When it is not, it is extremely difficult to find it.

Facebook is becoming the largest public square that humanity has ever known, partly thanks to photography. It is a seemingly insignificant trick that gave it the decisive advantage over other social networks: users can tag images with the names of the people photographed. It is clear that every photo is relevant to the person portrayed in it and to that person’s friends.

The tag gives the image the coordinates it needs to achieve the greatest scope of relevance. Amateur photography, the same one that years before had as its destination the dark drawer or the private album, becomes a very powerful tool to talk about our lives.

The new amateur photography

The question is what do fans now communicate with their images? Facebook’s success is linked to a key feature of human language: we talk to share information, to build alliances and loyalty circles, we talk to determine our place in the community. In other words, we talk to gossip.

Neuroscientists like Jonathan Haidt, the author of “The Happines Hypothesis,” say that gossip is such an essential part of human behavior that language may have evolved from the need to exchange information about others. This quote from Haidt illustrates how this powerful linguistic transaction works:

We are motivated to pass on information to our friends; sometimes we even say, “I can’t shut up, I have to tell someone. And when you pass on a juicy piece of gossip, what happens? Your friend’s reflex to reciprocate comes into play and she feels a certain pressure to return the favor. If she knows something, she’ll probably say, “Well, I heard that too…” Gossip incites gossip and allows us to track someone’s reputation without the need to directly witness someone’s bad behavior. Gossip is a game from which both parties benefit: it costs us nothing to share information and both benefit from receiving information.

If we continue with the analogy of Facebook as the largest public square that humanity has ever known, we can understand that information about others – gossip – is relevant to the people directly connected to the event, not to everyone. The tags that allow information to travel between “friends” achieve the very clear purpose of allowing us to hear the news amidst the noise of the square.

What do we tell through pictures? That we have friends. That we have fun. That we love or that we stop loving. That we are connected. That we travel and look. And of course, that we have something relevant to say, that we are good and interesting members of our community…

Expressing similar feelings through words is difficult or impossible. Gossip has to be rich, juicy to circulate quickly, and yet the word does not fulfill certain social functions that only pictures can fill. A picture portrays the most detailed aspects of our life in a wonderful way. A skilled reader can read in a picture our state of mind, our social class, our purchasing power, even know our tastes, what motivates us. By publishing our private photo album we are sharing the essential clues to our identity -and to our vulnerability.

Legions of voyeurs and exhibitionists populate the public square of the present, we reveal information to others so that they reveal information to us, following the ancestral pattern of gossip.

If gossiping is an essential aspect of human behavior, to feel that we belong to a community is a sine qua non of well-being, health, and happiness, as affirmed by that newest branch of neuroscience that has come to be called the Science of Happiness. The risks to privacy are perceived as minor when compared to the desire that we human beings have to belong.

The Library of Babel

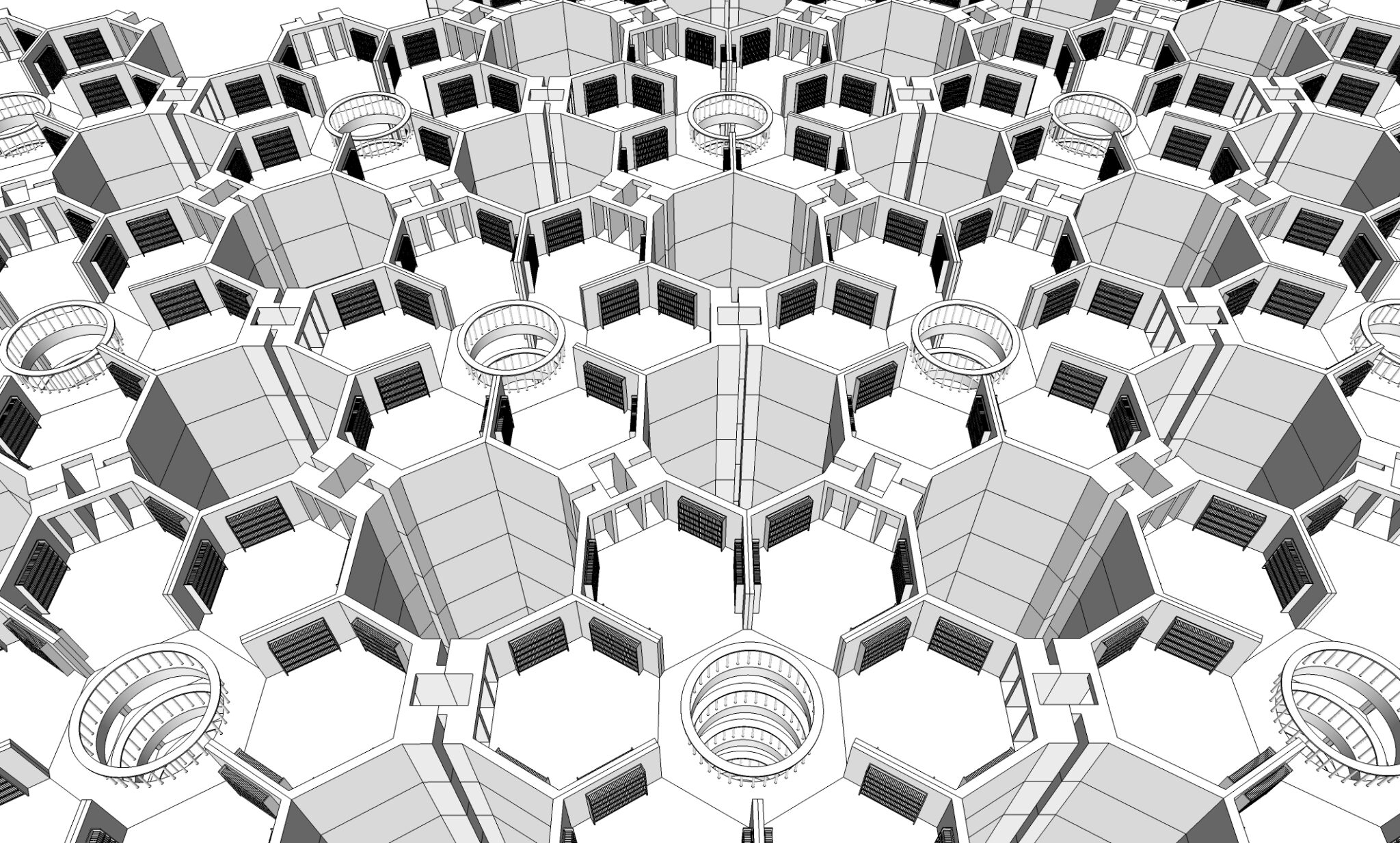

If Facebook is a large public square, the inter-network or network of networks, it is the closest thing to the Library of Babel that Borges described in such detail:

“The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite number, and perhaps infinite, of hexagonal galleries, with vast ventilation shafts in the middle, surrounded by very low railings (…) In the vestibule there is a mirror, which faithfully duplicates appearances. Men usually infer from this mirror that the Library is not infinite (if it really is, why this illusory duplication?).”

Computer networks are connected to larger ones, and so on until they constitute a network of networks that look at each other and through which it is possible to travel to any coordinate with the sole expression of an IP (Internet Protocol) number. In this extraordinary labyrinth, without beginning or end, all points are equidistant, you can reach from any place to any other place. It is curious to think how Borges imagined the need to install mirrors inside the great Library, the basic architecture of the network is full of mirror nodes that reflect and reiterate, and that are the backbone of the interconnection.

The inter-network is the largest repository of information, the most ambitious work of engineering ever built by human beings. This Library is so portentous that it is difficult for us to stop looking at it, trapped by its unlimited -and perhaps infinite- mirror. The fascination we feel for the inter-network is similar to that of Borges’ hero when he looks at the Aleph:

I saw a small, iridescent sphere of almost intolerable brilliance. At first I thought it was rotating; then I understood that this movement was an illusion produced by the vertiginous performances it contained (…)

I saw the populous sea, I saw the dawn and the afternoon, I saw the crowds of America, I saw a silvery spider web in the center of a black pyramid, I saw a broken labyrinth (it was London), I saw endless immediate eyes scrutinizing me as in a mirror, I saw all the mirrors of the planet and none reflected me (…)

Part of the fascination has its origin in the fact that the inter-network is also the human creature most similar to a living organism. It behaves according to the same rules that govern unpredictable weather patterns, the dispersion of pollen in water, the growth of a cell tissue, or the spread of a virus among diverse human populations. Its movements and growth appear random but are subject to mathematical rules embedded in the very nature of the world. In any case, this is what Albert-Lázsló Babarabási, the great expert in the Science of Networks, maintains.

The best time for photography, the worst time for photographers

Given the nature of the inter-network, all images are archived in the same virtual space and can all be viewed from any point. The fascination that the Aleph provokes in us also causes a deep paralysis, an essential incapacity to process an unlimited amount of data in the limited time we have. The most urgent issue in these times is to determine what is relevant and for whom, a very difficult issue to solve in the case of images, since if they have not been previously tagged or valued, they cannot be catalogued, searched or organized.

In the inter-network, relevance is determined by criteria and patterns that are very different from those that governed the life of images in the 20th century. The functions of photography, an extremely powerful and increasingly universal language, go far beyond those it had before the construction of the network of networks. Photos are used to express ideas and emotions, to monitor, document, denounce, inform, measure, explore, analyze, study, understand, move, inspire and of course, remember.

It is the best time for photography, there is no doubt about it – it has never had the vitality it has now, it has never been used by so many people at once. But it is the worst time for (professional) photographers.

If photography is an almost universal language, if more than 1.4 billion camera phones are going to be used this year, if almost everyone is able to express themselves through images, where is the role of professional photographers, of those who kept the secret of quality with deep zeal?

We all talk and write but few are paid to do so. The same will happen with photography. In a world where almost everyone can express themselves photographically, there will be very few who can make a living from photography. But the language of photography, revitalized by the participation of millions of new amateurs, will take exciting, renewing, revealing paths.

The natural mission of the professionals of photography in this transition stage -given the knowledge we have of the visual language- will be to help give meaning to the apparent chaos, to give importance to certain images and points of view, to try not to lose the visual sophistication we already acquired in the 20th century. We must help a new aesthetic to emerge that is capable of speaking properly of the new times. We professionals of photography have a dilemma: either we become leaders of change or we disappear, we cease to be relevant.

The power of numbers

There are three characteristics of digital files that I would like to highlight, out of the many that we can attribute to them:

a) They are infinitely reproducible. Digital files – including digitized images – are a collection of numbers that can be duplicated without any limit and without any loss of quality. Strictly speaking, every copy is an original. A negative or slide, on the other hand, loses quality with each copy.

b) They are portable – a digital file can be transported with great ease. It is clear that everything that can be transported digitally will be, since physical means of transport are expensive and inefficient.

c) They are flexible: once an image has been expressed numerically, it is infinitely malleable, adaptable and transformable.

These three characteristics are essential for understanding the path that the new photography will take. In the past, photographs were naturally scarce (there was an original to which a limited number of copies could be made), copies were difficult to transport, and their shape was determined by the tools used.

For example, if a photographer captured a black and white image, with a panchromatic film of certain characteristics, the possibilities of expressing that image were many, but there was no way to rescue the color.

With a raw digital file (RAW), which contains the sensor information, you can later decide whether the photo is to be expressed in colour or black and white, determine the brightness and contrast, and control any other known or unknown variables. This malleability calls into question that concept, so 20th century, that black and white photos are more artistic, or that the value of an image is proportional to the effort and technique of the photographer. Many of the aesthetic decisions will be made after the shot is taken.

The portability of images means, however, that it will be impossible to think about photography without also thinking about the inter-network. The channel of consumption and interconnection will define its uses and functions.

How do sensors “see”?

One of the most frequent conceptual errors is that modern digital sensors “see” in a certain way, in the same way as the analog films of the past did.

A Kodak Tri-X film or a Fuji Velvia film reproduced the world with the parameters dictated by its chemical composition. Each film “saw” the world in a certain way.

All digital sensors are black and white and can only give us values for the amount of light falling on each pixel. We were able to reconstruct the colour because we placed colour filters on top of the photoreceptors. The values generated by these sensors are just that: values, numbers. In order for them to make any sense we have to express them using formulas and agreements.

The first agreement is that the photos of the present should look like those of the past. All the algorithms used now aim to reproduce the aesthetics of the old 20th century films. But CCD or CMOS sensors are totally different in nature from a transparent roll covered with photosensitive salts. In fact they capture so much more, that to achieve the reassuring effect of the past we have to limit their ability to photograph invisible light (UV or infrared), we have to multiply the contrast they generate, we have to manipulate their sensitivity to certain wavelengths (colour) and we have to refocus the contours of objects.

This claim of photojournalism to photograph reality seems even more futile when we think of the amount of manipulation that these numbers have undergone, extracted from the sensor, to arrive at a visible image. What interpretation is true, if the very nature of a numerical file is its unlimited malleability? The digital “original” does not exist, there is only a collection of numbers that have to be reinterpreted or expressed in a visible format.

The primitive cameras of the present

Ramesh Raskar, my teacher at the Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) argues that today’s digital cameras are just a replica of the analog ones of the past. What the manufacturers have done is replace film with sensors, but the structure of the camera obscura (the lens that concentrates the rays, a dark space in between and a sensor or film at the other end) has remained identical. There are smaller cameras, with innovative shapes, but their internal structure has not changed.

According to Ramesh, we have not yet seen any profound changes in the way we capture images. The tool that changes everything is the computer and its ability to process information. But we haven’t yet fully discovered what the computer is going to be used for in the case of image processing…

Instead of taking advantage of the enormous amount of information that we can acquire and process through sensors and computers, we capture images in cameras that are very similar to analog ones, we discard much of the information so that they look the same as they did in the past, and then we mercilessly use Photoshop and its palette of kitsch effects to distort them.

In other words, we remain trapped in the logic and aesthetics of 20th century photography. We used tools a thousand times more powerful to do the same thing we did with film. And we think that if we add a layer of distortion through photoshop to that very familiar image, we have arrived at the future.

We can see the first examples of the effect of computers on what is often called augmented photography: sewn-in panoramic photos, high dynamic range photos, correction of geometric aberrations and distortions in the lens, images captured in very low light situations, the fact that you can capture moving images and still images with the same device. Thanks to the computer we have multiplied the sensitivity and capacity of traditional photography, but we still have a long way to go…

The four dimensions of geometry

We’re surrounded by cameras. The most common of all is the computer mouse, there are billions of them in the world. That optical device we see under most mice is a small camera usually with 18×18 pixels that compares the variations of intensity/voltage and allows the computer to know in which direction we want to move the cursor.

Another camera we are surrounded by is the alarm movement sensor. It is a two-pixel camera. When there is no voltage variation between the two, we know that everything is static, but if there is a slight variation between the receivers, we know that there was movement.

It is clear, especially when we think of medical imaging, that it is not essential to have the structure of the camera obscura (lens, dark space and sensor) to build images. A medical ultrasound device is capable of generating images from the sound waves reflected by the different organs. What we are doing in the case of ultrasound is building an image through the mathematical processing of many samples: we project sound waves and measure the time they take to return.

Something similar happens with a CT (Computerized Axial Tomography). We place an X-ray camera and spin it at very high speed around the body. It is equivalent to placing many cameras and shooting them from many angles. By means of computational processes we are able to infer the spaces that were not photographed (it is not efficient to take pictures from all angles) and in that way we can build a three-dimensional model of the body.

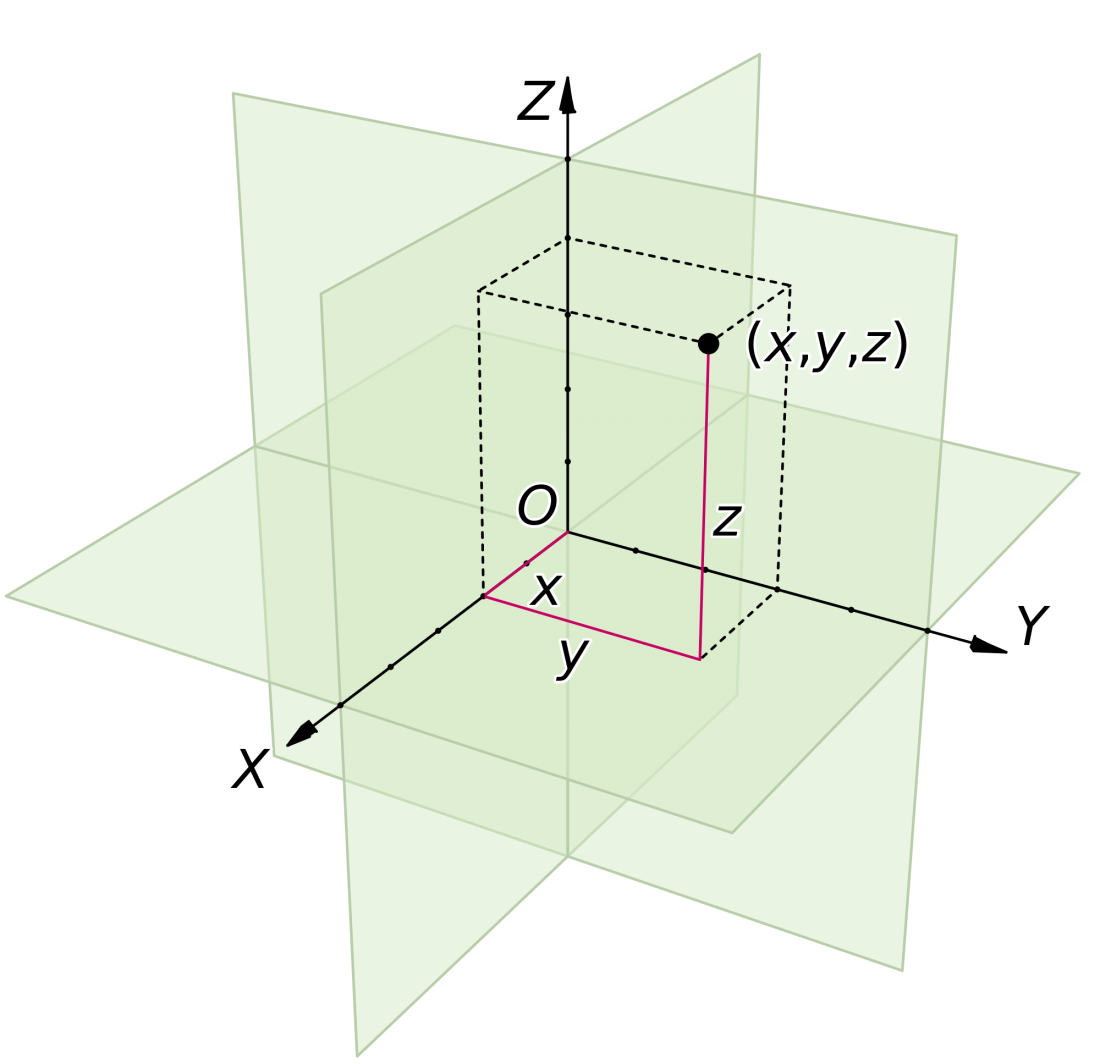

The first lesson, when one starts thinking about the computational processing of images, is that the 3 dimensions of a Cartesian plane (x, y, z) are not enough to understand any space. It is true that with these three values we can name any point in space, but we always need a fourth geometric dimension that corresponds to the perspective of the viewer.

In order to understand a space from a computational point of view, we always need to know from where we are looking at it. For the information from the CT or ultrasound to be useful, we need to know from where we are measuring the points we are capturing.

So to represent the world we need a minimum of four dimensions. And if we consider that to graph the light, we also need four dimensions, we come to the conclusion that to accurately describe the world and the light that illuminates it we need a minimum of eight dimensions.

The purpose of this sub-chapter is simply to remind us that we are surrounded by cameras of all kinds, which capture different segments of the electromagnetic spectrum and which record space in different ways, from the primitive two-pixel motion sensor to the CT, that very powerful four-dimensional X-ray camera.

Thanks to the computational power we can connect several cameras, organize them in “arrays” or rows (if you are interested in the subject, look for lightfield photography or camera arrays). If with two cameras we can do stereoscopic photography, with dozens of cameras we can build giant, much brighter virtual lenses, we can look around objects, collect precise information about dimensions and spaces, and we can decide what to focus on and the depth of field after the shot. Just imagine how the possibilities are expanded by “photographing” segments of the electromagnetic spectrum that are not visible like X-rays, infrared or ultraviolet light, etc.

All the information we acquire through sensors we have to process mathematically to build visible images. This is why in order to imagine the photography of the future it is indispensable to think about the role that computers have and will have.

The connected device

According to Ramesh Raskar, most cameras – which only serve that function – will disappear in less than 5 years. Cell phone cameras will be of sufficient quality to replace them almost completely. There will still be some professional cameras or those with technical or scientific uses.

The camera we find in an iPhone costs a few dollars and has a simple and cheap plastic lens. How can this micro device compete with a larger camera with expensive and sophisticated lenses?

The first principle of the new computer photography is that if we know how an image was encoded, we can decode it. For example, if we know the optical defects of the plastic lens, we can correct them and get a great quality, almost as good as that of a more sophisticated camera. With the inclusion of more powerful microprocessors we will achieve perfect images from simple cameras.

With the reduced cost of these mini cameras it will be possible to install camera arrays in a cell phone to build virtually very bright lenses and to resynthesize the focus, exposure, depth perception (stereoscopic image). Almost all decisions will be made after the shot is taken. The Lytro, the first commercial camera to use the principles of lightfields photography, already allows us to focus after shooting.

But the issue of quality in cell phones – which in a few years will be completely solved – is not as important as the extraordinary power that a network camera gives us. Connected photography is a new language that allows us to communicate in real time, to comment on what attracts us, what excites us, what makes us passionate, what makes us angry, and what allows us to be part of a community.

The trends

In closing, I want to tie up a few loose ends and mention some trends:

a) Professional photographers have lost the exclusivity of photographic language. Billions of people can now take high quality photos and also share them, that is, use them beyond the private sphere.

b) The democratization of the language of photography -together with the fact that we can share images cheaply and efficiently- will allow the emergence of new discourses, new uses, new aesthetics, new themes.

c) Photographs will find new spaces of relevance thanks to the fact that they will be labelled with information about the people photographed, the geographical coordinates (GPS), the historical situations, the context, the approval of curators, of guilds, the scientific or technical validation. Remember that an unlabeled or unvalidated photograph is very difficult to find. The labels will define the relevance of an image, they will give it the coordinates to travel in the inexhaustible labyrinth of the network.

d) As with any other language, what we say by means of “connected photography” will have a direct relationship with society -its searches and needs-, rather than with the technology used. That is, it matters more what is said than how.

e) It is impossible to think about the future of photography without considering the transformative role of the internet. All photography will be somehow present in the network.

f) Images are infinitely reproducible, portable and malleable. Images will circulate freely and be transformed freely after shooting, because it is in their digital nature to do so.

g) The negligible cost of taking pictures means that they will be present in all aspects of our lives, from surveillance, to remote sensing, to documentation and measurement. Cameras will be in every appliance or object, from cars to coffee machines to textiles to eyeglasses and in the future even in contact lenses.

(h) The cameras of the present remain trapped in the aesthetics of the past. When they are released and develop the full potential of the digital, they will serve to broaden our perception of the world, to see it in entirely new ways. Rather than recording what our eyes already record, they will serve us to see beyond, further, smaller, around objects, at invisible wavelengths, to reconstruct whole scenes from segments, to understand multidimensional spaces. They will serve us to increase and complete the human experience.

i) There will be no technological difference between the still image and the moving image. In fact, the most important decision will be which part of the information is used, which part is relevant.

Photography is born linked to technology. Of all languages, it is the one that most needs a technical platform to exist. But it is not the technique that gives it its raison d’être or its importance. The deep fascination it exerts on us is related to the fact that it delves into the most irremediable mystery: time. It is a language to share our perceptions and understandings, our joys and sorrows, to speak of the rich and multifaceted human experience.